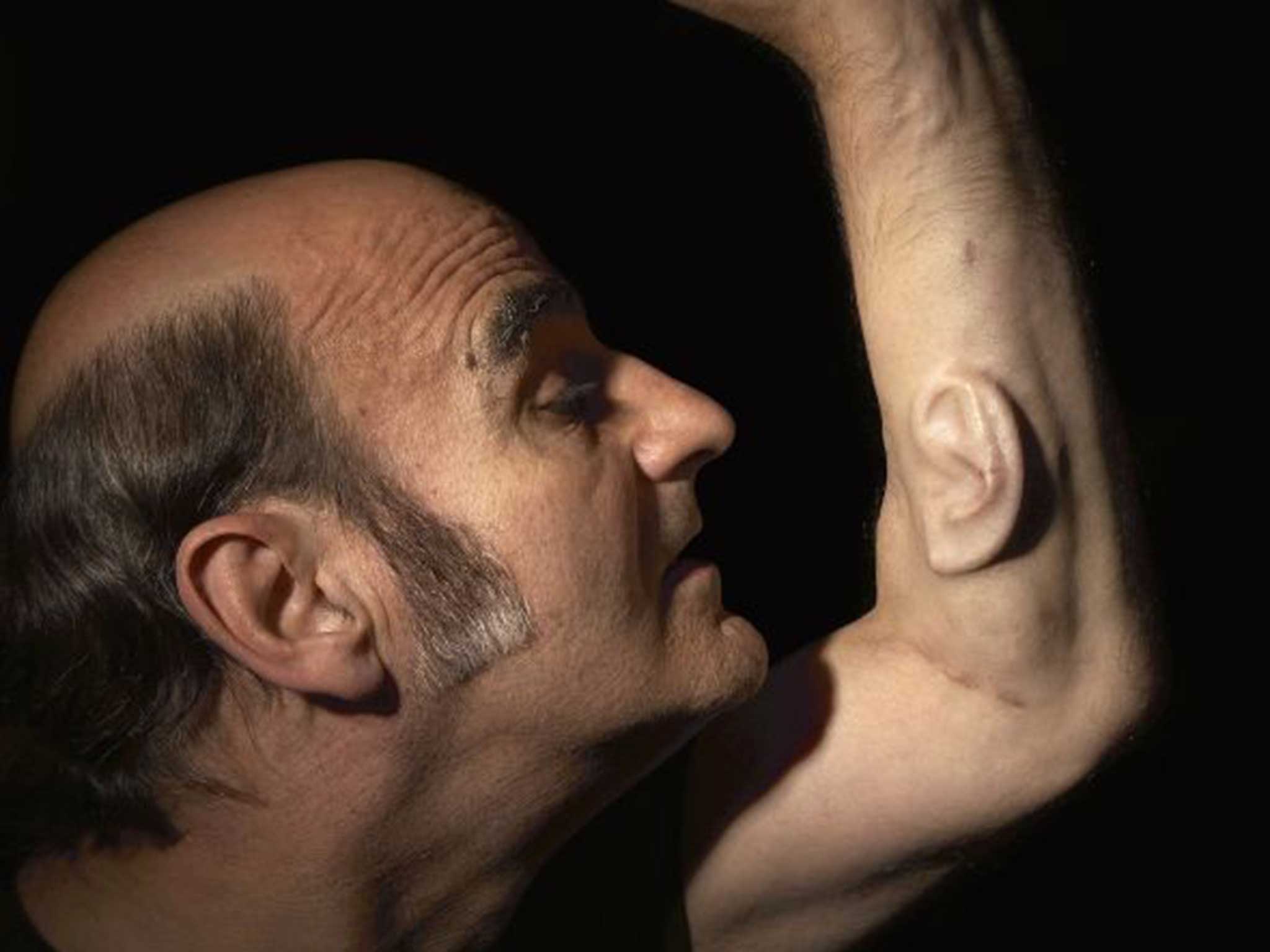

In a recent session, we were given an image of Australia-based performance artist known as Stelarc (born Stelios Arcadiou), with his now famous 3rd ear. The image was a provocation for us to respond to in groups.

From my research using Stelarc’s website I have found: the ear is made from Medpor, a porous material used in medical reconstruction. The shape of an ear was scaffolded before being surgically implanted onto Stelarc’s forearm, after the skin in the area had been stretched to accommodate it. Using a porous material allows Stelarc’s own flesh to grow through the material as it heals, so the ear now has a blood supply. It took Stelarc 10 years to find a surgeon willing to carry out the operations. He also wishes to experiment with an organic method, planning to grow the lobe of the ear from his own stem-cells.

The ear acts as a augmentation of the human form, disrupting the familiar and pushing the boundaries of the body. In this respect it relates to Surrealism, compelling the viewer through shock to question their assumptions.

By utilising the body as a material, the work also links to Performance Art, and especially it’s tendency towards pain and endurance. By undergoing surgery, Stelarc consented to an amount of pain in the name of aesthetic experimentation.

The work is also contemporary, as it raises questions around groundbreaking medical and technological interventions: the rise of cyborg humans. As we increasingly live our lives through augmented and digital reality, so too do our bodies become more artificial, from familiar interventions such as false teeth and contact lenses, to more extreme developments such as plastic surgery, pacemakers and location tracking chips.

In a digitised world, what is the meaning of our evolutionary architecture? We can now engineer new organs that better support us to navigate the technological and globalised world we inhabit, so what are the potential results of this?

Stelarc further enhances this reading of the work through his ambition to have a microphone embedded in the ear, which anyone around the world can listen to live 24/7 through an internet broadcast. One microphone has already had to be removed due to infection, but he reports that it was working and the intention is to replace it.

Through this addition, Stelarc makes the ear ‘hear’ it’s surroundings. However, this seems to disrupt the ear as actually it ‘speaks’ to the audience, who must listen via the the internet but cannot speak back. Stelarc collapses his private and public realms, but the conversation is only one way. This could act as a metaphor for digitised relationships in general, such as through social media: everyone is talking but noone is listening.

In response to these ideas and conversations, the group I worked with produced this piece:

An expanded body with peeled-apart layers, facing away from itself, and disembodied organs strewn around. Collaborator on the piece Damyon Garrity made this video response, which shows the multiple layers:

References:

STELARC (2017) EAR ON ARM. [Online] Available at: http://stelarc.org/?catID=20242 [Accessed: 10 November 2016].